The dimly lit office is in a run down building, with a small signage anyone can easily miss. The 30-square feet reception area has no room for visitors.

Operating under the department of atomic energy, which is headed by the Prime Minister, IREL is today 75 years old. And yet, till about a few months ago, no one would have heard about this ‘miniratna’—a category of profitable public sector enterprises with greater financial and operational autonomy.

After decades, the company, formerly known as the Indian Rare Earths Ltd, is experiencing a rare moment of recognition—tasked with mining rare earth minerals, its work is of great importance to the defence establishment, and key to India’s quest to accomplish a net zero carbon footprint by 2070.

The minerals the company mines are called ‘rare’ not because they are scarce but because it is difficult to find economically viable concentrated deposits. Rare earth minerals are used in the making of magnets, critical components in the motors that power electric vehicles and wind turbines. They are also used in lasers, MRI machines, vehicle oxygen sensors, ceramics and paint pigments.

In addition, IREL manufactures rare earth magnets, from a plant in Visakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh. Turns out, the company is the sole Indian manufacturer of such magnets. And now, there is a global shortage, which is threatening to derail India’s electric vehicle (EV) story. China is the leader in making these magnets and a new Chinese policy restricts its exports, a retaliatory measure against the aggressive tariff policies of US President Donald Trump.

By June, India’s large automobile companies, such as Maruti Suzuki and Bajaj Auto, said that they had stocks of rare earth magnets that would last until July. On 11 June, Reuters reported that Maruti Suzuki had cut near-term production targets for its maiden EV, e-Vitara, by two-thirds because of rare earth magnet shortages.

As production of EVs is tied to India’s net zero emissions target, there are long-term repercussions to such demand-supply mismatch.

Who’s running the show?

The Indian government realizes the pivotal role IREL can play.

“IREL is now interacting with several ministries, including mining, commerce, and heavy industries. They are all looking to secure rare earth supplies,” Sarada Bhushan Mohanty, the company’s director of finance, told Mint. “All our pending projects are under review for faster execution,” he added.

The company has been without a full-time chairman since November 2024 but Mohanty has been picked as the next chief by the public enterprises selection board. His appointment, though, is subject to the approval of the appointment committee of cabinet.

A cost accountant and a management graduate, Mohanty isn’t your typical public sector executive. Earlier, he had worked with private sector companies—Tata Steel Long Products and Vedanta. Before joining IREL, three years ago, he also served at the National Aluminium Company Ltd, a state-owned aluminium maker.

“India is among the oldest producers of rare earth elements but a combination of factors held back development of the industry,” he said. “But, given the importance of these minerals to modern technology, a realization set in—there is no other option but to be self-reliant.”

If India indeed started early, when and how did IREL lose its way? Its history reads like a roller coaster ride, across seven decades.

Homi Bhabha’s baby

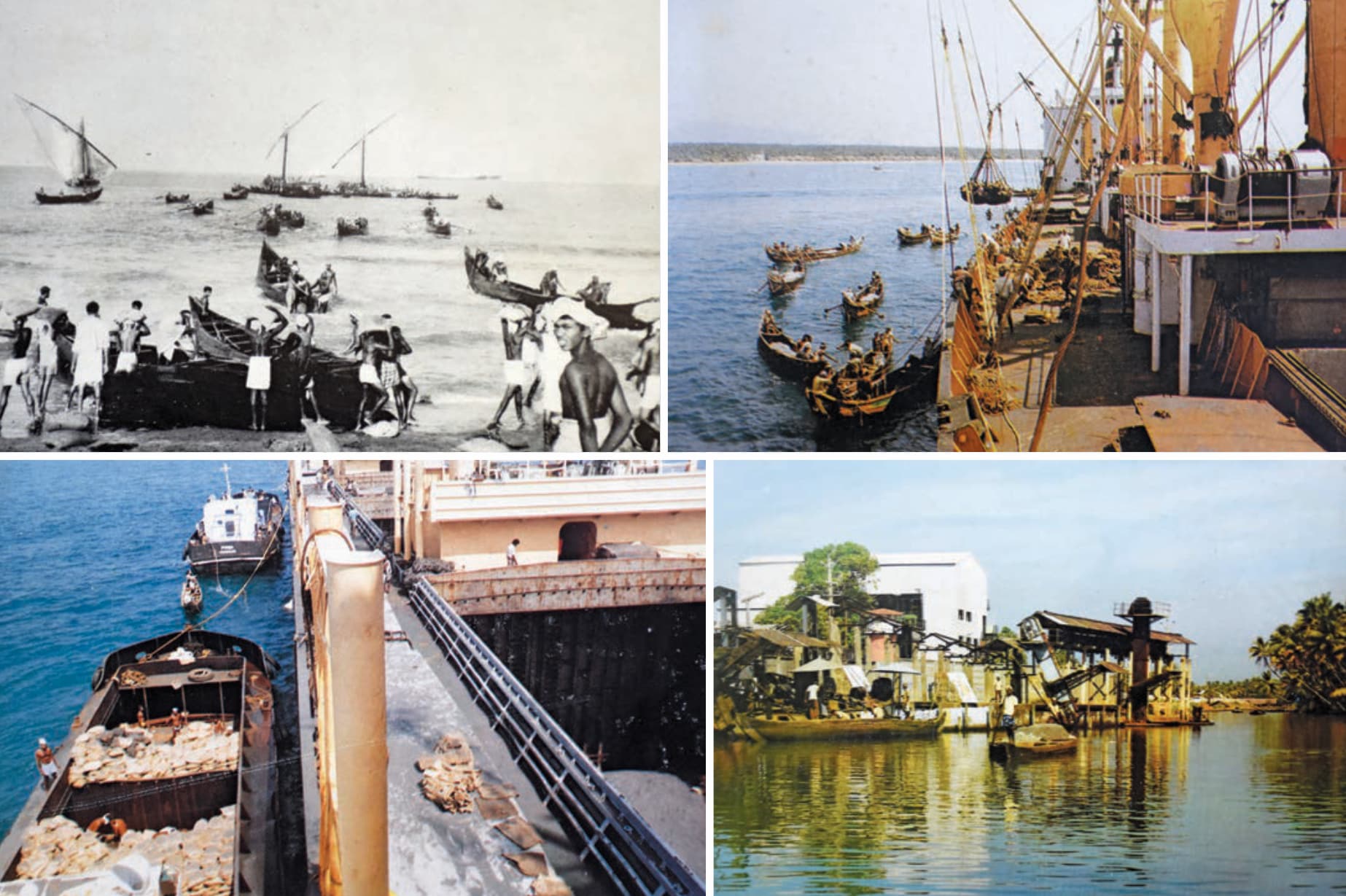

India’s rare earth exports predated independence, when radioactive material was accidentally discovered in the beach sands of Kerala. In 1909, a German chemist, Herr Schomberg, noticed glittery substances stuck to coir ropes imported from India and established that it was monazite, a reddish-brown phosphate mineral. Monazite was a source of thorium, a slightly radioactive metal, used in making gas mantles in the era that predated electric bulbs.

Subsequently, India started exporting beach sand and its extract to Germany and the UK.

Homi Jehangir Bhabha, often referred to as the father of the Indian nuclear programme, set up Indian Rare Earths Ltd, IREL’s predecessor, in 1950. He did so to bolster India’s energy security as radioactive thorium had the potential to be used as fuel in nuclear reactors. Back then, the government also decided to stop all exports of rare earth elements.

View Full Image

In fact, policymakers across the world had realized its economic, perhaps geopolitical significance. A year earlier, in 1949, the first deposits of rare earth elements were discovered in the US, in southern California’s Clark Mountain Range. When production started in 1952, the US government bought the entire mine’s production to stockpile for its future use in electronics and defence applications.

In the first decade of its existence, IREL had a poor run even though it set up its own processing unit and took over other units run by erstwhile British companies. The use of thorium dwindled as gas mantles were replaced by electric bulbs and a by-product of thorium production, RE chloride, a compound with applications in material science, found no takers. This led to huge problems with disposal.

By the mid-60s, a resolve to find customers for RE chloride led to Japanese companies who found the compound useful in their fast growing electronic industry. Subsequently, another rare earth element, Europium, found a use case in television screens.

IREL’s prospects blossomed. By the 1970s, the company had expanded capacities and was producing RE chloride and Zircon, a mineral used in the uranium fuel lines of nuclear power plants.

Until the late 1990s, the public sector company continued to mix-and-match its products as per requirements of its overseas customers; the domestic market remained small. Its turnover, in 1999-2000, was ₹214 crore. Exports accounted for 85% of the production.

View Full Image

“Being under the department of atomic energy, IREL was technology focussed and kept modifying its product portfolio to meet customer demand. To that extent, it was highly market centric,” said Deependra Singh, who retired as chairman and managing director in November 2024 and oversaw the company’s 75th year celebrations.

Activism on the beach

If IREL ended the last century well, its fortunes changed immediately after. After India liberalized its business policies starting in the early 1990s, the private sector was allowed to export rare earth element ores, and their extracts, barring thorium. Several private companies popped up along the coast of Kerala and Odisha, and they mostly exported the raw material—beach sand.

This led to activism in the southern states, especially Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka, where local groups wanted export of sand to be stopped. State governments got involved and mining, subsequently, became more controlled. According to a report published by IREL, this led to the cancellation of several of its mining rights. Stricter environmental laws also meant delays in its processes to obtain the raw material.

We always walk a tightrope as Indian environmental laws are stringent.

— S.B. Mohanty

Typically, the company leases land patches in beaches or sanded areas for 11 months, either from the state or private owners. It does so after obtaining local clearances and then proceeds to process the sand. With its mobile shifting machines, it extracts what it needs and puts 90% of the sand back into the same area. Usually, as part of the deal, the company also engages in afforestation in the land.

“We always walk a tightrope as Indian environmental laws are stringent,” Mohanty said.

But what cooked the public sector company’s case was China’s increasing domination of the sector towards the end of the century.

China’s win

Until China came into the picture, in the late 1980s, the private sector in the US produced more than 90% of the world’s rare earth elements.

The Chinese government started subsidising local companies and that made many US-based firms unviable, leading to their closure. A second factor led to the decline of the industry in the US— authorities found contaminated water from the California mines leaking into the soil. This reportedly caused radioactive contamination. Regulations subsequently became more stringent, increasing the cost of operations.

View Full Image

Eventually, aided by Edward Nixon, a brother of President Richard Nixon, the US company, Unocal Corporation, began exporting ore to China in 1997. The Chinese firms, in turn, processed and manufactured the rare earth elements, shipping it back to the US at lower costs.

Over time, China sourced its own ore, thus, controlling the process end-to-end. This led to the closure of US mines.

“China has integrated its rare earth elements industry across the board—from sourcing raw materials to downstream production of rare earth magnets for the user industry,” said Mohanty. That led to lower costs and countries around the word found it convenient to just import such components.

By 2005, the equation had flipped: China now processed 90% of rare earth ore and produced 70% of the rare earth elements.

Meanwhile, the cheap availability of finished goods and a toughening socio-political situation in the home market, led to a decline in the production at IREL. A cyclone in Odisha in 2014 also disrupted operations—the company posted a loss of over ₹100 crore in 2015-16, its first loss in over a decade.

Policy moves

It is not the first time that China restricted rare earth elements export. It did so in 2010 which caused a bigger upheaval among user countries like the US and Japan. The US, EU and Japan complained to the World Trade Organization (WTO) saying that China’s restrictions were unfair under its rules. On its part, China argued that excessive mining was putting a huge strain on its environment and depleting its own resources. China, however, lost the WTO case and subsequently lifted its export restrictions in 2015.

That jolt may have had repercussions in India, too. In 2016, India’s long term planning body, NITI Aayog, drafted its initial policy for electric vehicles. Securing rare earth markets was an essential part of that policy. In particular, in 2017, V.K. Saraswat, a member of NITI Aayog, proposed increased investment and policy support for India’s rare earth sector.

View Full Image

“A core committee was formed by NITI Aayog which had representation from IREL, too. To that extent, there was a reasonably good understanding of the problems associated with rare earth elements and in particular, rare earth magnets, within the government,” said Deependra Singh.

Indian EV makers, meanwhile, found it convenient to import.

“Though we localized most of our parts, there were some inputs like rare earth magnets, which we couldn’t, as there was no ecosystem to make them,” Suhas Rajkumar, founder and CEO of electric scooter maker Simple Energy, said. “Importing from China was not the easiest but quickest alternative.”

This month, the Union government announced a ₹1,345 crore subsidy scheme to encourage the manufacturing of rare earth magnets within the country. Though a critical component, the market today is small—the annual consumption of these magnets hovers around 850 tons and is worth ₹350 crore, according to IREL estimates.

Therefore, small and medium size companies could be interested in making them. IREL is expected to play an important role in arranging technology for these manufacturers, and getting the projects off the ground.

Sand to rock

IREL’s performance has picked up significantly over the last few years. In 2023-24, the company posted revenue of ₹2,104 crore, growing 11% over the previous year. Net profits jumped 25% to ₹1,012 crore.

During the year, the company started production of permanent magnets at its plant in Vizag. It also started with the production of rare earth metals at the Rare Earth Metal & Titanium Theme Park, Bhopal.

Nonetheless, the company has identified a challenge that could restrict its growth—the Indian ores of rare earth elements have poor concentration of metals, leading to higher recovery costs. This is especially so for metal extracted from sand sources.

IREL has a three pronged solution to the problem. Firstly, it has identified a second source—the hard rocks of Rajasthan. These mines are under development. Secondly, it plans to secure imports from more countries, as China has done. China gets most of its raw material from Myanmar, while Australia is being touted as a source for India. Thirdly, as recommended by Saraswat, IREL plans to help in the recovery of used magnets by recycling. China recycles 80% of its magnets.

But one crucial link, pointed out earlier by Suhas Rajkumar, is still missing. India’s ecosystem lacks the technology to make rare earth magnets. And entrepreneurs are absent, too.

“We need companies to come up with the engineering and execution skills; put up facilities to make these magnets,” Mohanty said.

In its Odisha factory, IREL is making pilot sized demonstration plants available for entrepreneurs. Additionally, it is also working with the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, a nuclear research and development facility, to shortlist more technologies that could be used for magnet making.

“Half of our problems will be solved if India ties-up for better quality ores, like China did with Myanmar,” Mohanty said.

IREL, the forgotten public sector company, finally has a seat at the table. It can consult ministries, policy makers, help other companies get up to speed, and execute India’s rare earth mineral strategy, all by itself.

Key Takeaways

- IREL, which operates under the department of atomic energy, is experiencing a rare moment of recognition.

- The company is key to India’s net zero carbon footprint goals.

- The public sector firm is tasked with mining rare earth minerals. In addition, it manufactures rare earth magnets.

- Such magnets are in short supply because of export restrictions from China.

- This month, the Union government announced a ₹1,345 crore subsidy scheme to encourage the manufacturing of rare earth magnets within the country.

- Apart from extracting metals from sand sources, IREL has identified a second source—the hard rocks of Rajasthan.

- It also plans to secure raw materials from countries other than China.

IREL India Ltd,rare earth minerals,electric vehicles,rare earth magnets,net zero carbon footprint,irel india,rare earth minerals india,rare earth magnets india,india rare earth magnets,miniratna company india,miniratna psu,miniratna,rare earth shortage india,india net zero 2070,critical minerals india,critical minerals,rare earth magnet manufacturing india,rare earth magnet manufacturing,strategic minerals india interest,strategic minerals india,public sector enterprises india,india china rare earth trade,thorium production india,electric vehicle raw materials india,electric vehicle market,electric vehicle,Indian Rare Earths Ltd,Maruti Suzuki,Bajaj Auto,net zero india,net zero emissions goals,homi bhabha

#India #rare #earth #magnets #forgotten #PSU #holds #key