Hours later, Taliban troops walked into the capital after America pulled its last forces out of Afghanistan. The Foreign Minister soon fled the country, seeking refuge in Turkey. Bakhtari didn’t. Defying the Taliban’s order dismissing her, she remained in the embassy and still continues to represent her country in Vienna while fighting for the rights of women and girls in Afghanistan as the last Afghan woman envoy in the world.

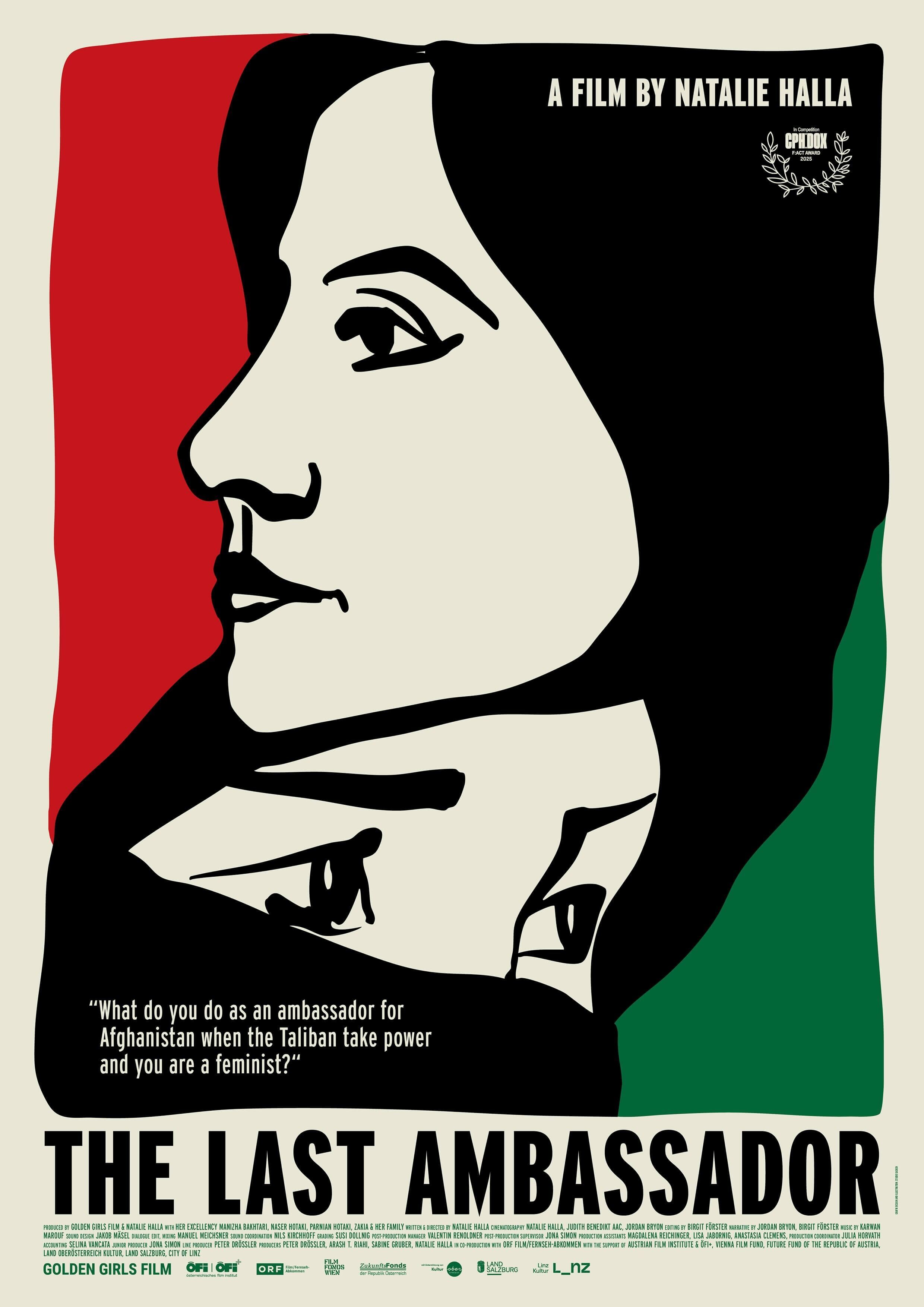

Last week, Bakhtari, 52, was given a standing ovation by the audience at the Copenhagen International Documentary Film Festival (CPH:DOX) in Denmark where a new documentary on her had its world premiere. The Last Ambassador, directed by Austrian filmmaker Natalie Halla, shows a determined diplomat refusing to give up and launching a lasting resistance against the Taliban on the global stage.

The 80-minute film, which premiered at CPH:DOX on March 22, spans the long journey of Bakhtari from her position as an envoy of the Ashraf Ghani government in Afghanistan to an ambassador that the Taliban doesn’t want. As she campaigns against international recognition for the Taliban regime, Bakhtari also sets up a clandestine learning network in Afghanistan for girls banned from schools.

“Manizha Bakhtari is still the Ambassador of Afghanistan to Austria. She is also still the representative of Afghanistan before the United Nations and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),” says Halla, a lawyer-turned filmmaker who first saw Bakhtari on television news as she called the Taliban terrorists a few days after the fall of Kabul on August 15, 2021.

Legal limbo

The Taliban takeover in 2021 left Afghan embassies worldwide in a legal limbo as some envoys started cooperating with them while others refused. A few others dared to openly oppose the Taliban. Among them was Afghanistan’s last remaining woman ambassador, Bakhtari. It was a move that would invite swift punishment from the Taliban.

Soon Bakhtari received a letter signed by a Human Resources director in Kabul relieving her of duties. Her response too was prompt: “I am not taking orders from you, Mister,” she told herself, characterising the HR director as “probably a Taliban gunman”.

As the legal vacuum continued, Bakhtari was asked on Austrian television whom she represented in Europe. “It is important to represent the people of Afghanistan. That is a mission for us now,” she replied, emphasising her resignation would happen only when the Taliban receive international recognition.

Situated on a busy thoroughfare, the Afghan embassy in Vienna was like any other mission until August 2021. The embassy would go on to pay a heavy price for its defiance. Several employees were let go after the Taliban stopped the flow of funds, forcing embassy drivers to cover vacant posts.

On the third day of the fall of Kabul, the Taliban held a press conference, promising the world they will allow women to work “within the framework of Sharia” and declaring “women are an essential element of the society and we respect them”. “The Taliban were selling the idea that they had changed,” says Bakhtari in the film, which is dedicated to the women and girls of Afghanistan.

In the days following their proclamation to the world, women in Afghanistan began protesting they weren’t allowed back to work and girls crying they were denied entry to schools.

Managing mission

Bakhtari, a former ambassador to the Nordic countries, was watching the events back home with rapt attention. Five months after the Taliban takeover, she moved the embassy to an affordable house in Vienna, managing the mission with income from consular services. She also launched a campaign in Afghanistan called Dukhtaran, which means daughters in Persian, to secretly provide lessons to girls banned from schools.

Raising the pitch of resistance, Bakhtari also hosted a summit, called Vienna Conference, gathering Afghan representatives from all ethnic and religious groups in the Austrian capital in April 2023 to forge a united strategy against the Taliban. Among them were many women activists as well as Ahmad Massoud, the son of Ahmad Shah Massoud, who fought the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

The Taliban hit back by blacklisting the Vienna embassy and declaring documents issued by it as invalid. Bakhtari also has to deal with death threats and abuse online from Taliban supporters. In July last year, the OECD bloc of developed countries bestowed the White Ribbon Award on Bakhtari for defending the rights of women in Afghanistan. A month later, the Taliban introduced a series of new laws that escalated their policy of gender apartheid, effectively erasing women from public life.

More than three years after leading resistance against the Taliban, Bakhtari, who taught journalism at the Kabul University before joining the Afghan Foreign Ministry as Chief of Staff in 2007, is optimistic. “Our efforts have prevented international recognition of the Taliban regime,” beams Bakhtari, who became Afghan’s ambassador to the Nordic countries in 2009. “The Taliban won’t stay forever. They will be gone one day.”

Though no nation has recognised the Taliban government, many countries, including India, have held talks with the regime. In January this year, Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri met the Taliban’s acting foreign minister Amir Khan Muttaqi in Dubai, the first high-level engagement with the Taliban since the fall of Kabul.

Raising resistance

Bakhtari, one of three daughters of well-respected Afghan poet Wasef Bakhtari, found herself on the side of those resisting fundamentalism early in her life following an arranged marriage at 19 to businessman Naser Hotaki. When her father published his new book of poetry in exile in the US, he dedicated it to her. “For my daughter, who is better than 100 sons,” read the dedication.

“Peace is not the absence of war, but the presence of justice,” Bakhtari is shown saying in the film, which she didn’t want to be made initially. “When I first approached her with the idea of a documentary on her, she said very diplomatically and politely, ‘No,'” recalls the film’s director Halla.

Produced by Golden Girls Film, a Vienna-based collective that also produced the 2025 documentary Girls & Gods, about a group of women in Europe and the US pushing back against power structures, The Last Ambassador exposes the enablers of the Taliban return, including America, which secretly signed the Doha Deal in 2020 with the Taliban paving the way for its return. For Afghans, it was a deal that ignored women’s rights to study and work, and the collective achievement of the previous two decades without the Taliban.

Halla, who convinced Bakhtari about the importance of making the film weeks after the Taliban takeover, shot the movie, which is in Dari language and English, for nearly three years following her in the embassy and outside. “I did not expect the embassy to continue work till even now,” says the filmmaker. “They receive no money from the Foreign Ministry in Afghanistan, so they survive how they can. For them it’s not about the money, but the importance of keeping the embassy open as a place of resistance against the Taliban. And a platform to advocate for the rights of women and girls.”

Afghanistan,Taliban,women rights,Manizha Bakhtari,documentary film

#Afghanistans #Ambassador #Austria #confronting #Taliban #fighting #oppression #women #country #World #News