The moment Maureen Sullivan, then just 12-years-old and holding a dark secret that had dominated her young life, decided to confide in her school teacher, a nun named Sister Veronica, changed the course of her life forever – but not in the way she’d hoped.

Little did the vulnerable schoolgirl know then, but speaking out about the horrific sexual abuse she’d suffered at the hands of her step-father from the age of eight would unlock a world even more treacherous for her.

Uttering the words out loud, she tells the Daily Mail, evoked new trauma, after she was sent to Ireland’s notorious Magdalene Laundries, where she would be cruelly shunned and ostracised from other children so as not to ‘corrupt’ them with her tainted childhood.

Now 73, and living in Carlow, in Ireland’s south-east, Maureen explains how her already difficult young life unravelled further in just a few moments of honesty, saying: ‘They looked at me as if I was the devil, I was the sinner…not my step-dad’.

The Catholic church, she says, quickly buried the allegation, explaining away the abuse as a ‘weak moment’, because Maureen wasn’t biologically his daughter.

‘The way the priest looked at it, he was a good man to take my mother on with three children.’

Far from being the rescue she’d longed for, Maureen would spend her early teenage years in an institution that would tarnish much of her adult life.

There were approximately ten Magdalene Laundries operating in Ireland from the 18th to the late 20th centuries. The first, an Anglican institution, opened in Dublin in 1767.

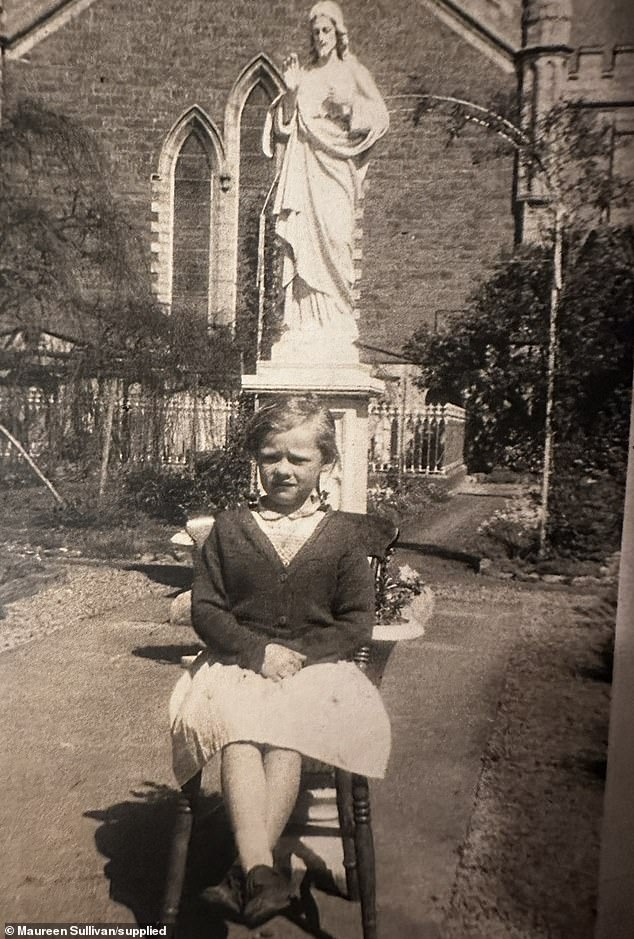

Maureen Sullivan (pictured), 73, who now lives in Carlow, in Ireland’s south-east, was just 12 when she was sent to a Magdalene Laundry in the town of New Ross, after she disclosed she’d been abused by her step-father to a nun at her school

Often called ‘asylums’, the laundries would effectively imprison women, forcing them to perform unpaid laundry work, sewing, cleaning, and cooking for local businesses, the church, or the state, as penance for violating ‘moral codes’.

Between 1922 and 1996 alone, around 10,000 women and girls are thought to have entered the institutions for a wide range of reasons. Residents included girls who had been orphaned or rejected by foster parents, sexual abuse victims, those who’d carried a baby out of wedlock, or young women who were perceived to be ‘promiscuous’.

Now an author and campaigner for the Justice for Magdalenes group, Maureen was held against her will at a Magdalene Laundry in New Ross, a town in County Wexford, which was run by the Good Shepherd religious order, for four brutal years from 1964.

The young adolescent would endure abuse at the hands of the nuns who worked there, including being forcibly trapped in a tiny tunnel behind the property’s church for eight hours without access to food or a toilet.

Due to her young age, Maureen was concealed within the institution – her identity was altered, her name changed to ‘Frances’ and her hair cut, taking away, she says, any sense of belonging and individuality she once had.

Despite her obvious absence from school, she continued to be marked as present on attendance records in Carlow, preventing authorities from discovering her disappearance.

One of 13 siblings, she had virtually no contact with her mother, who visited her at the laundries just four times in as many years.

After enduring the sexual abuse from the age of eight to 12, she finally plucked up the courage to confide in her teacher – but was quickly removed from her family and sent to the laundry, so as not to ‘corrupt’ others with her trauma (Maureen pictured as a child)

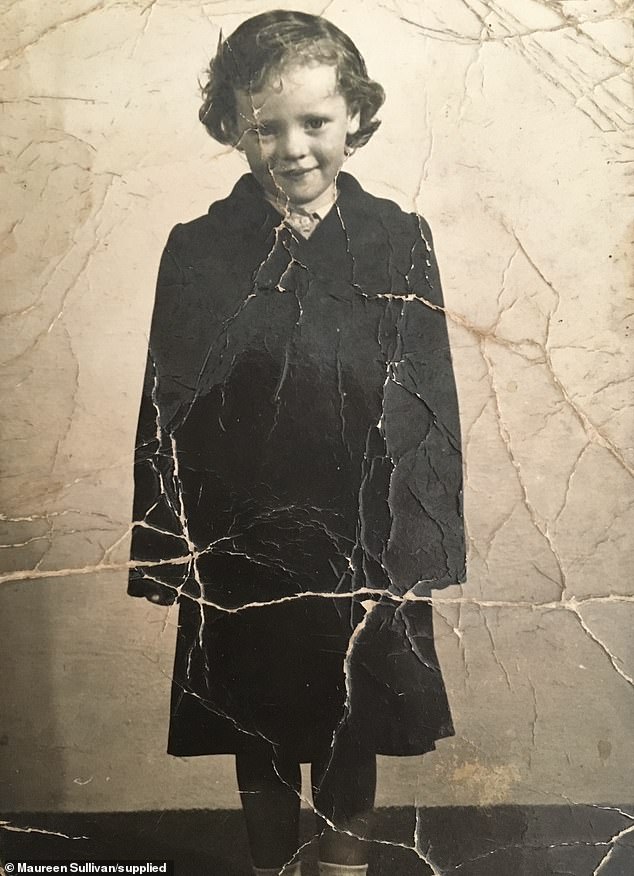

Because she was young, Maureen (pictured in childhood) was concealed within the institution, which was run by a Catholic religious order known as The Good Shepherd. Her identity was altered, her name changed to ‘Frances’ and her hair cut

Describing the day that had sealed her confinement to the laundry, she describes how a nun at her Carlow school, Sister Veronica, had expressed concern for her wellbeing, noting that she appeared unusually pale and had become emotionally withdrawn.

‘She said “come on up to the office with me”, and there was a box of Black Magic chocolates. These were poor times. Very poor times. So this was a luxury,’ Maureen recalls.

Sister Veronica told her she had become ‘very concerned’ after seeing how low she appeared, noting that she was never ‘clean like the other girls’ and always had her ‘head down’.

As she sat in the nun’s office eating the chocolates, Maureen was gradually able to open up about her life at home and the abuse she had been subjected to by her step-father, who she refers to now as Marty, which isn’t his real name.

She told the teacher she was unhappy at home and asked if she could live with her grandmother to escape her step-father.

Shortly afterwards, Maureen was asked to wait outside the office, where a priest came to speak with her.

She recounts what Sister Veronica told her moments later: ‘They said, “Maureen, we’re going to send you to a nice school tomorrow and you can come back to Carlow with your head held high”. [These] were her very words. You know, I always remembered it.’

While the kind nun ‘meant well’ and ‘really believed in her heart’ that she was going to the nearby school of St Aidan’s, the priest decided that she should be sent to the laundry in New Ross.

The following morning, Maureen’s mother was informed of the abuse and told her daughter would be taken away ‘for her own safety’.

Her step-father portrayed her as a liar. He had coerced her throughout the years of abuse into remaining silent by making threats that she would never see her beloved grandmother again if she spoke out.

Maureen explains: ‘I never told my mother, all I could think was “I need to be able to see my granny”‘.

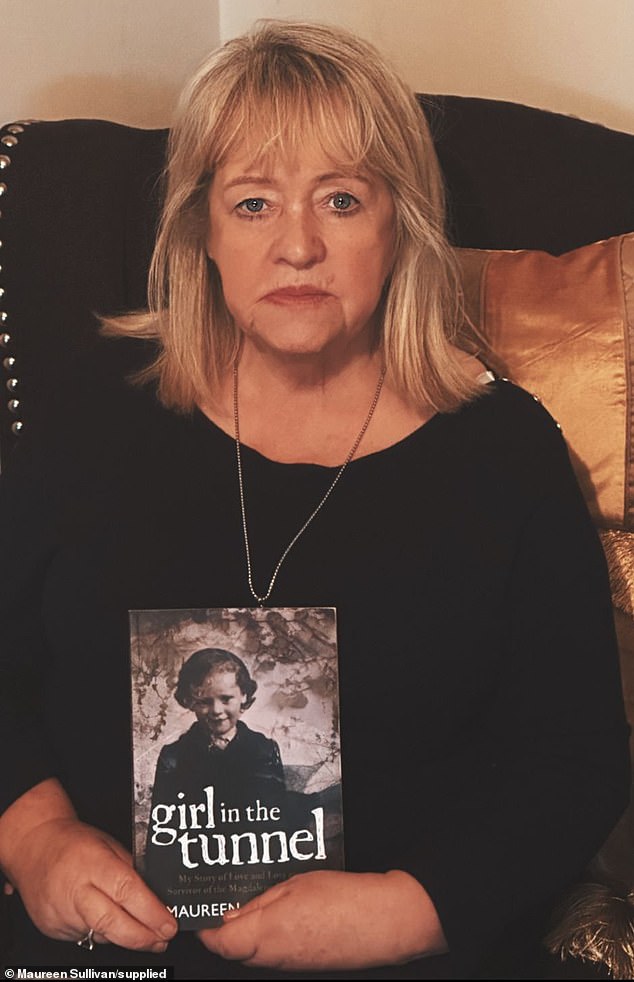

At the age of 35, she attempted to take her own life and ended up in hospital – where she was given access to the therapy she received would change her life (Pictured with the book she published in 2023 recounting her experiences at the Magdalene Laundry)

For four years in the 1960s, Maureen, then a young adolescent, was forced to endure hard labour, before she finally escaped as a 16-year-old (pictured as a younger child)

On the day of her departure, her mother was told a bus would be collecting Maureen to take her to a ‘new school’ in New Ross.

Maureen says: ‘I remember my mother ran down the road, I could hear her panting bless her, to buy me a pencil case. I never had a pencil case before, I just had a little paper bag with my pencils in it. We couldn’t afford pencil cases at the time.’

The moment she arrived at the institution, she ‘knew straight away that something was horribly wrong’. Maureen remembers how her new pencil case was taken off her by the nuns and she pleaded with them to get it back.

Instead of a school education, Maureen endured hard labour and long days. She was woken at 6am to clean corridors, windows, and doors before attending Mass and having breakfast.

The rest of the day was spent working in the laundry. After tea at 5pm, she attended so-called ‘recreation’, where she was forced to make rosary beads for Lourdes, Rome, and other holy places.

The women were not allowed to speak to each other as they worked. Exhausted, they would go to bed at 8pm, ready to start it all over again the next day.

Weekends would bring further arduous toil, cleaning the church or the nuns’ apartments. There was no compensation for the work the women carried out.

As the youngest girl in the workhouse, Maureen would be hidden during routine inspection visits. At the time, the laws in Ireland allowed children to leave school at 14 only if they had a job.

Describing the horror of being incarcerated in a tunnel for up to eight hours, she recalls: ‘It was early in the morning, we weren’t long at work. The nun grabbed me and said “come on the men in the suits are coming”, and I was put down in the tunnel.

‘I had to go to the toilet, I was embarrassed. I had no way out of there. That place frightened the life out of me and I was terrified.’

Maureen says the nuns forgot about her and she remained trapped with no idea what time it was, only remembering that it was ‘late at night’ when she was eventually let out, and past dinnertime. She never received an apology.

Maureen wasn’t allowed to mix with the children attending St Aidan’s, which was next to the laundry, though she didn’t understand why at the time. Years later, she met with one of the nuns to seek answers.

The author and campaigner’s early life trauma left her depressed in her mid thirties after she started getting flashbacks of the abuse she had endured (Maureen speaking at a Magdalene Survivors Together press conference in 2013)

The sister explained that the belief at the time was that Maureen might ‘corrupt the innocence’ of the other children if she interacted with them.

Maureen says she asked the nun: “‘Sister, are you telling me they put me into the laundry because they thought I would tell the other children what my step-father had done to me?’

The nun nodded, she says, replying: ‘It was wrong… but yes, that’s what they did.’

After her time at New Ross, she was transferred to another of the Magdalene asylums, in Athy, County Kildare, and then to a home for the blind on Merrion Road in Dublin.

At 16, Maureen was finally allowed to leave, she took the boat to London with her brother Patrick where the pair decided to build a new life.

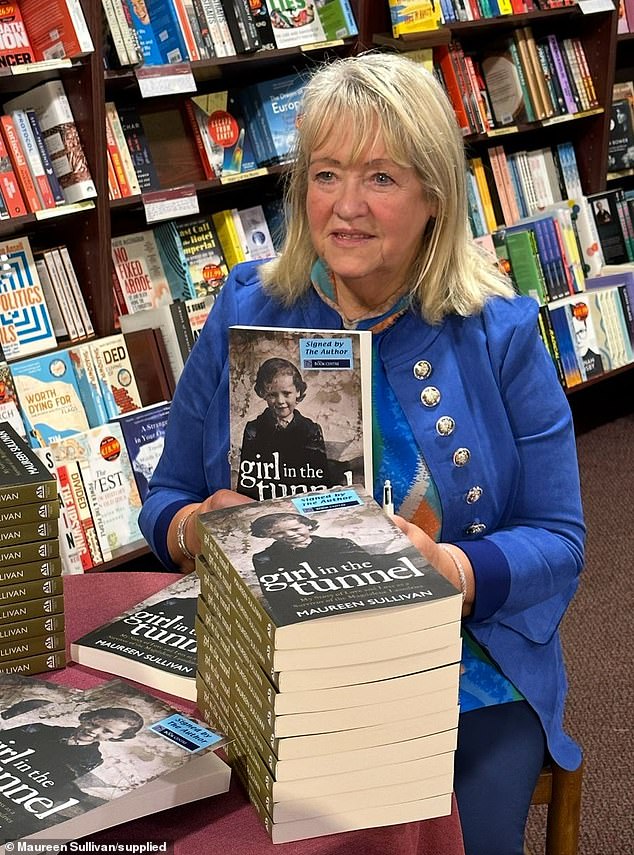

Maureen, pictured at a book signing two years ago, eventually returned to Carlow to live – and has been an active member of campaign groups that fought for an apology over the Magdalene Laundry abuse

However, with no money and nowhere to live they slept in Argyll Square, Kings Cross, with no sleeping bags or pillows. After two months they found the Irish Centre in Camden Town, which helped them find a room.

‘I’m very lucky that my life didn’t turn out that I was murdered or forced into prostitution, drugs or alcohol, I’m very, very lucky. Some angel was looking after me.

‘I was offered drugs in London, but I knew not to take them, I slept in squats, it took me years to get on my feet.’

She married soon after she arrived in London and had a daughter when she was 19 but she struggled to parent. A son came 15 years later.

Without an education, Maureen was limited to jobs in laundries and restaurants, she became depressed and started getting flashbacks of the abuse.

At the age of 35, she attempted to take her own life and ended up in hospital where she was offered therapy.

She adds: ‘I had no education. I worked in Woolworths, I was so run down, it was a struggle, I couldn’t hold down a relationship. I was depressed, I went to take my own life.

‘I started talking about what happened to me. I had a fantastic counsellor, I told her I didn’t want to be here anymore and she told me I needed to open up more. She said, “I’m not going to harm you or send you away anywhere, you need to talk to me.'”

‘I told her the truth and it was like a breath of fresh air, it was healing, all this stuff that I had hid inside of me and carried with me every day.’

Reflecting on her time in the laundries, Maureen tells the Daily Mail what hurt her most was the realisation that, beneath their religious robes, the nuns were still women, yet they had chosen not to protect her, a child who had been sexually abused.

She adds: ‘How can women be so cruel to a little girl that has been through an awful, awful time?’

Marina Gambold (left) and Maureen Sullivan (centre) of campaign group Magdalene Survivors Together leaving Leinster House in Dublin after hearing Taoiseach Enda Kenny’s state apology in 2013

Her mother, who had ten children by Marty, left him soon after Maureen was placed in the laundry – but she kept the abuse a secret to ‘protect’ her other children.

Maureen explains one of Marty’s biological daughters also claimed to have been sexually abused by him and ended up dying by suicide.

‘She made the statement herself before she passed that he was abusing her, she didn’t want to be buried with him.’

In 1995, Maureen moved back to Ireland – around the same time that Magdalene Laundries became the subject of intense scrutiny as others shared their stories.

The last laundry ceased operation on October 25th, 1996.

Maureen joined Justice for Magdalenes, a group that helped bring about an apology from the Irish State over past abuse – more than a quarter of those who spent time in the laundries had been sent there by the government.

In February 2013, Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Enda Kenny issued a formal apology on behalf of the state for its role in the Magdalene Laundries.

Delivering a speech in the Dáil (Irish parliament), he said: ‘For 90 years Ireland subjected these women, and their experience, to a profound indifference,’ he said.

‘By any standards it was a cruel and pitiless Ireland, distinctly lacking in mercy. We swapped our public scruples for a solid public apparatus.’

In 2022, the Irish Government’s compensation scheme had paid out approximately €32.8 million to 814 survivors of the laundries.

Reflecting on the apology, Maureen says: ‘That was better than any money they gave us, because they gave us pittance anyway. That was the most important thing, that apology meant the world.’

Asked if the church has taken any accountability for its role in the Magdalene Laundries, she adds: ‘No, and it won’t, they never will, they will never admit their role in it.’

Since releasing her book in 2023 detailing her harrowing early life, entitled Girl in the Tunnel, Maureen says the response has been mixed. While some have applauded her bravery, others still want to keep her silent.

Despite possessing official documents confirming her time in the laundries and her Confirmation there, some individuals have dismissed Maureen’s account as untrue.

She recalls an encounter in a shop following the release of her book. A woman approached her and said: ‘I knew your step-father, I always found him to be a very nice man.’

She asked how the woman knew him; she admitted, ‘Well, I didn’t really know him really… but he was always at Mass. Such a holy man.’

Maureen listened quietly before walking away. Reflecting on the exchange, she says, ‘What a thing to say to a survivor of abuse.’

Marty died when Maureen was in her thirties without being subjected to any criminal investigation. He asked to see his step-daughter one last time while he was in hospital. She confronted him about the abuse, saying she would ‘never forgive him’.

He told her he was only getting her ‘ready for the outside world’, at which point Maureen left the room.

Four religious orders who ran the laundries after 1992, the Religious Sisters of Charity, the Sisters of Mercy, the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity and the Good Shepherd Sisters, have ‘declined’ to make a financial contribution to the Magdalene Laundries Restorative Justice Ex Gratia Scheme, the Department of Children confirmed in 2022 to The Irish Times.

The Congregation of the Good Shepherd, said in a statement to the Daily Mail last week: ‘The Good Shepherd Sisters remain focused on providing whatever support they can to women and children who were in their care and continue to offer help and pastoral support wherever possible.

‘They support victims and survivors in several ways. The Congregation has made financial contributions to the Towards Healing support service since its inception almost 30 years ago.

‘This means that any victim or survivor who requires support has access to a free, confidential, independent counselling service for as long as they need.

‘Many former residents and their family members remain in contact with and have good relations with individual Sisters. This is encouraged and acknowledged as an essential encounter in the healing process.

‘The Good Shepherd Sisters have co-operated fully with several historical inquiries, including detailed testimony from many of its members and by providing extensive files and documentation. We continue to engage with ongoing investigations.

‘We do not comment publicly on individual cases, but we strongly encourage anyone in need to contact us directly.’

The laundries isn’t the only macabre story to have come to light in recent decades.

In the past, Ireland’s strict Catholic morality made it deeply shameful to become pregnant before marriage, and women would be rejected by their families and society as sinful.

Amongst the most shocking cases was the discovery in 2017 of a mass septic tank containing the skeletons of 800 babies, found at the former site of The Tuam Mother and Baby Home in County Galway.

The home was one of ten institutions in which an estimated 35,000 unmarried pregnant women – so-called ‘fallen women’ – were sent to.

The dead babies are thought to have been secretly buried beside the home for single mothers and their children over a period of 36 years, ending in the 1960s.

The home operated from 1925 to 1961, run by a Catholic order of nuns called the Sisters of Bon Secours. Almost 800 children, aged between two days and nine years, died at the home between 1925 and 1961.

dailymail,news,Old Femail

#abused #stepfather #age #confided #teacher #put #home #hid #tunnel #treated #devil