It was just before 10am on a June morning in 1972 when Douglas Robertson heard a series of ear-splitting bangs reverberate through the wooden hull of his family’s sailing boat, the Lucette.

He knew instantly they signalled disaster – and he was right. The 43ft schooner on which the 18-year-old, his siblings and parents, plus a hitchhiker bound for New Zealand, had been sailing around the world for 18 months had just been attacked by three killer whales.

Within moments, the Lucette began to sink into the vast Pacific Ocean, her timbers groaning as water poured through the shattered planking.

The crew had only seconds to act, scrambling to grab whatever belongings they could before clambering into a rubber life raft.

They were 200 miles from the Galápagos Islands, adrift with no maps, compass or navigation instruments, only ten days’ supply of water, three days of emergency rations and a limitless horizon of sea. Nobody knew they were missing.

What followed was an extraordinary fight for life – six people, including 11-year-old twins Neil and Sandy – battling sharks, storms, hunger and despair amid a merciless ocean that seemed intent on swallowing them whole.

‘To this day, I don’t really know how we survived,’ Douglas says. ‘Every night we’d watch the sun go down and wonder if we’d still be here to see it rise in the morning. We never knew if we’d make it through the night.’

Incredibly, the family of five, plus passenger Robin Williams, 23, survived for 37 nights, most of them crammed into a salvaged 9ft fibreglass dinghy after their life raft also sank.

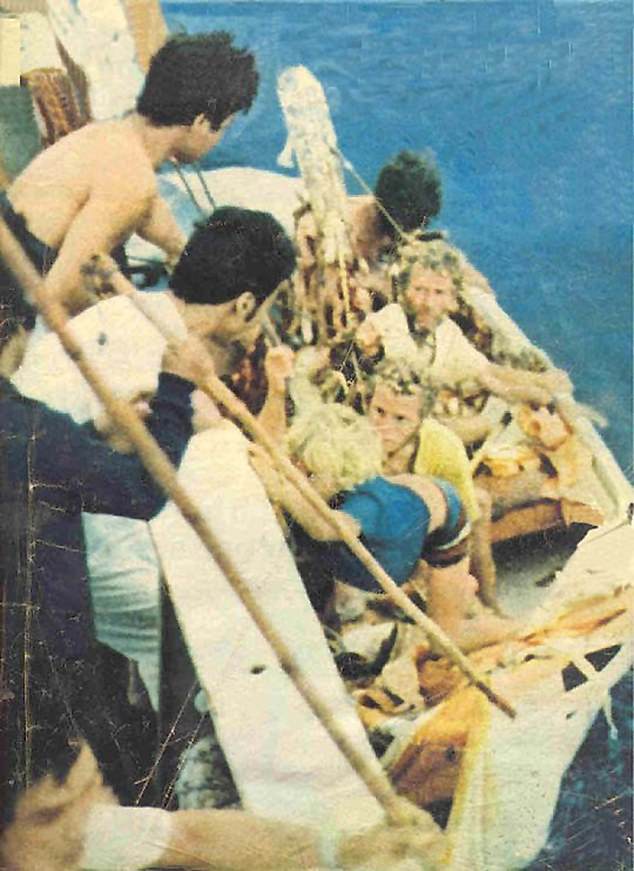

The Robertson family (pictured) had been sailing around the world for 18 months when their boat was attacked by three killer whales

When they were finally rescued by the astonished crew of a Japanese fishing trawler, they had drifted and rowed more than 750 miles.

Now, more than half a century later, the gripping story of those weeks at sea has been transformed into an immersive eight-part podcast by Blanchard House, in which the Robertson siblings and Robin relive their ordeal in their own words.

‘It’s the highest fight you can have,’ Douglas, now 71, reflects. ‘Your only goal every single day is just to stay alive. And something like that does shape you. It made me fearless. When people say, “We can’t do this”, I always think, “Why not?”’

Today, father-of-five Douglas, whose eldest daughter is named Lucette in honour of the adventure that nearly cost him his life, lives in Barnet, north London, with his third wife and works as an accountant, having spent many years at sea as a navigating cadet.

But as a boy, he was raised in Staffordshire by his father Dougal, an irascible former sea captain, and his mother Linda, a nurse. ‘They’d met and married in Hong Kong but, because people do the stupidest things, they decided to buy a dairy farm in the Staffordshire countryside,’ Douglas laughs. ‘The trouble was, they didn’t have a clue how to run it.’

With four children, including eldest daughter Anne, life was hand-to-mouth and Dougal, frustrated by the humdrum routine and economic realities of farming, grew restless.

‘We lived in the middle of nowhere,’ Douglas recalls. ‘And who put us there? My dad. Then he decided we were uneducated halfwits who needed an education in the university of life, although that was just a cock and bull story to justify his own wanderlust.’

Dougal’s chance for adventure came after the family heard a radio programme about Robin Knox-Johnston’s solo circumnavigation of the globe in the late 1960s. ‘My brother Neil said, “Daddy’s a sailor. Why don’t we sail around the world?” And

Dougal thought, this is it, this is his way out,’ Douglas says.

Within months, he had sold the farm, bought the Lucette, a 50-year-old wooden schooner, and announced that the Robertsons were going to sea. ‘My mum was full of doubt and pretty much everyone thought we were mad,’ Douglas remembers, ‘But once Dad was fixed on something, that was that. I think us kids were just swept up in the excitement and the sheer audacity of it all.’

The family spent three months refitting the Lucette in Falmouth, Cornwall. Dougal never gave them a sailing lesson, though he did insist they all have their appendixes removed so they could rule out any medical dramas brought on by cases of appendicitis in the middle of the ocean. Linda quietly stocked the boat with tins of food, medical supplies and books for the children’s lessons.

Finally, on a cloudless January morning in 1971, they set sail from Falmouth Harbour. ‘Dad was shouting “Yeehaw!” and I remember Anne and I looking at each other thinking, “You’ve just given the game away. This is all about you,”’ Douglas says.

Either way, it was a wildly ambitious plan for a crew of amateurs, yet they adapted quickly and there were many magical moments as the family crossed the Atlantic, cruised the Caribbean and sailed into Miami, where they stayed for several weeks, taking odd jobs to pay for provisions and repairs. By then, they had finally acquired a life raft – no thanks to Dougal. ‘We’d befriended an Icelandic family who insisted on giving us their spare, saying they couldn’t bear to see us go any further without one,’ says Douglas. ‘Dad refused it, saying the best lifeboat is the one you’re on. But they persevered and told him they weren’t giving it to him but to his children. Thank God they did, because without it, we wouldn’t be here today.’

As it was, the Robertsons were a family member down when the Lucette left the Caribbean for New Zealand via the Panama Canal. Anne stayed behind, having fallen in love in the Bahamas. Her berth was taken by Robin, who paid a token fare to join them, as they headed south.

They had sailed round the Galápagos and were en route to the Marquesas Islands in the South Pacific when the killer whales struck.

‘I put my head down the hatch – Dad was already ankle-deep in water – and then I heard this big gushing sound behind me,’ Douglas recalls. ‘It was three killer whales, one with its head split open, blood pouring into the water. Dad was up to his knees and shouted, “Abandon ship!” I said, “To where? This isn’t Miami Marina! We’re in the middle of the Pacific!”’

As the Lucette went down, Dougal yelled for his son to haul the untested life raft overboard. ‘I was terrified the whales would eat us,’ Douglas says. ‘I thought, that’s how I’m going to die. We didn’t even know if the raft would work.’

Miraculously, it did. But chaos reigned as the family tried to board it. At one point, Linda was trapped on a railing of the sinking Lucette by her housecoat. Neil tried to go back to get his teddy bear. Robin, in his panic, stood on the gunwale of Lucette’s small dinghy, Ednamair, and flooded it – although somehow they managed to salvage it and tie it to the raft.

‘I was the last one in,’ Douglas says quietly. ‘I remember checking to see if I still had my legs because you don’t feel the bite. I grabbed bits of flotsam as they floated past – an orange, mum’s sewing basket – which later turned out to be vital tools.’

As they bobbed in the heaving sea, Douglas remembers his mum urging the terrified family to hold hands and say the Lord’s Prayer. Dougal refused.

The family are rescued by Japanese fishermen on July 23, 1972

‘He said he didn’t believe in God,’ Douglas recalls. ‘I said, “For God’s sake, can’t you just pray with us?” And he said, “If there’s a God, he’ll know I don’t mean it.” He never stopped being Dougal.’

Only later did the children learn that, in those first shocking hours, Linda and Dougal made a solemn pact that whatever it took, they would get their boys back to land. Collectively, the marooned crew also made another, grimmer vow: none of them would ever resort to eating each other.

After a long discussion, Dougal decided to head north for the Doldrums, where the trade winds meet, creating thunderstorms which would give them a supply of fresh water. Using an oar, a paddle and a makeshift sail, they turned the Ednamair into a tug to tow the raft, allowing them to inch their way north.

On day six, with rations gone, they watched helplessly as a ship passed, ignoring their flare. ‘That was a desperate low,’ Douglas says. ‘We’d banked everything on being rescued. When it didn’t happen, dad said we had to save ourselves. He decided we’d sail to America – 75 days away. It seemed impossible.’

The raft leaked badly and, when the bellows broke, the men had to inflate it by mouth. They caught flying fish, a large edible species called Dorado and, eventually, a turtle, which became their main source of food, with the blood drunk for its hydrating qualities. In time, they learned that Dorado eyeballs were a source of fresh water and took to sucking them whole. Otherwise, they frequently survived on one sip of water a day. ‘The thirst was horrendous,’ says Douglas.

The saltwater was equally merciless. They were often forced to sit chest-deep in seawater, as the raft was susceptible to flooding, leaving their bodies covered in sores and boils.

‘Fear was constant,’ Douglas adds. ‘You can park fear for a while, but the moment you drop your guard, it floods back. This was our world now, and you could be dead on the next wave. But you couldn’t think about dying – you had to think about the next task: bail the raft, catch a fish, make it through another hour.’

For days, it didn’t rain. Then, on the 13th or 14th day, it poured. ‘It was an Alleluia moment,’ Douglas says. ‘We caught gallons of water in our mouths and in every container we had. For the first time in days, we weren’t dying of thirst.’

Yet another trial lay ahead. On day 17, the life raft finally disintegrated beneath them. ‘Life had been miserable on the raft, but at least it protected us from the sun. Now we had no choice but to move into the Ednamair, which we weren’t sure would take our weight.’

It did, barely. ‘If you saw it, you wouldn’t believe six people could fit in that tiny dinghy,’ Douglas says. ‘We were so close to the water, we could see fish swimming underneath us. Birds landed on the mast, sharks followed us – it felt like we’d become part of the ocean itself.’

That ocean threw everything at them. On day 22, a violent storm raged for 24 hours, flooding the dinghy and forcing them to bail continuously. They rode 20ft swells and once felt the thud of a huge shark bumping the hull. ‘I remember looking at my family one day and they looked like human remains,’ Douglas says. Through it all, Linda was their anchor. ‘Dougal was our leader, but mum was the one who kept us going,’ Douglas recalls. ‘She talked to us, sang to us, patched our ragged clothes. She gave us the will to keep fighting.’

By the sixth week, they were all emaciated. The twins, Neil and Sandy, were dangerously weak. Having spotted the Pole Star, meaning they were back in the North Hemisphere, Dougal estimated they were about 350 miles from land – 15 days’ rowing if they could keep going. ‘But there was no guarantee the twins would last that long, especially Sandy, who had a terrible cough,’ Douglas says.

Then, on day 38, a miracle. A ship appeared on the horizon, the Toka Maru II, a Japanese fishing trawler bound for the Panama Canal. Dougal fired their last flare and this time someone spotted it.

‘There was a prolonged whistle, then we watched with our hearts in our mouths as the ship changed course,’ says Douglas.

Within ten minutes, the ship was alongside, though the rescue was perilous. Sharks circled the dinghy as the exhausted castaways reached for helping hands, while the remaining occupants tried to keep it from capsizing.

‘Only mums do this,’ Douglas laughs. ‘She’d saved a set of clothes for us to be rescued in. I remember her saying, “Put your shirt on, Douglas.” Even then, she wanted us to look presentable.’

One by one they were hauled aboard, only to find that their legs were so cramped from weeks in the dinghy they could barely stand. ‘Neil looked back at the Ednamair and said, “It wasn’t that bad, was it?” Almost as soon as we were rescued, we missed that daily fight,’ Douglas says.

Four days later, the family arrived in Panama to a blaze of international publicity, prompted by a telegram sent to shore by the Toka Maru’s captain: ‘Six stranded Britons saved.’

The British Embassy arranged their return home. Once there, with no house to go to, the Robertsons drifted between relatives and friends. ‘It was surreal,’ Douglas says. ‘Sandy put it best. He said, “Two months after we were shipwrecked, I was back in school.” None of us could believe it.’

Restless, Douglas soon returned to sea as a cadet, while back home, his parents’ marriage did not survive the strain. Within a year, they were divorced, though Dougal bought Linda a house with the proceeds from his bestselling book about the shipwreck.

‘I think it weighed heavily on them,’ Douglas reflects. ‘That they’d put us at such risk.’

Neil agrees and to this day believes his father was reckless.

But Sandy and Douglas feel only gratitude for their father’s madcap scheme. ‘He had his weaknesses and his failings, but he was my dad,’ Douglas says. ‘And every day of my life I thank him for what he did – because what we experienced was fantastic. For me, there’s nothing to forgive.’

Adrift is an Apple Original podcast, produced by Blanchard House. Listen from Monday, November 10

dailymail,news

#promised #eat #Adrift #days #Pacific #boat #sunk #killer #whales #British #family #endured #sharks #storms #drinking #turtle #blood #survive